Bernard Ntahondi

The Bantu word “Boma” was used by the German colonial administration for their government administrative centres throughout German East Africa. Many historical Bomas can still be found throughout Tanzania. The Old Boma is the oldest surviving building in Dar es Salaam, dating back to the 1860s when the city was first established under Sultan Sayyid Majid bin Said of Zanzibar. The building thus represents one of the foundation stones of the city and is inseparably linked with its history. Originally intended as a guesthouse for the Sultan’s visitors and family, its completion was interrupted after the Sultan’s death in 1870. The structure remained largely unfinished and was eventually abandoned.

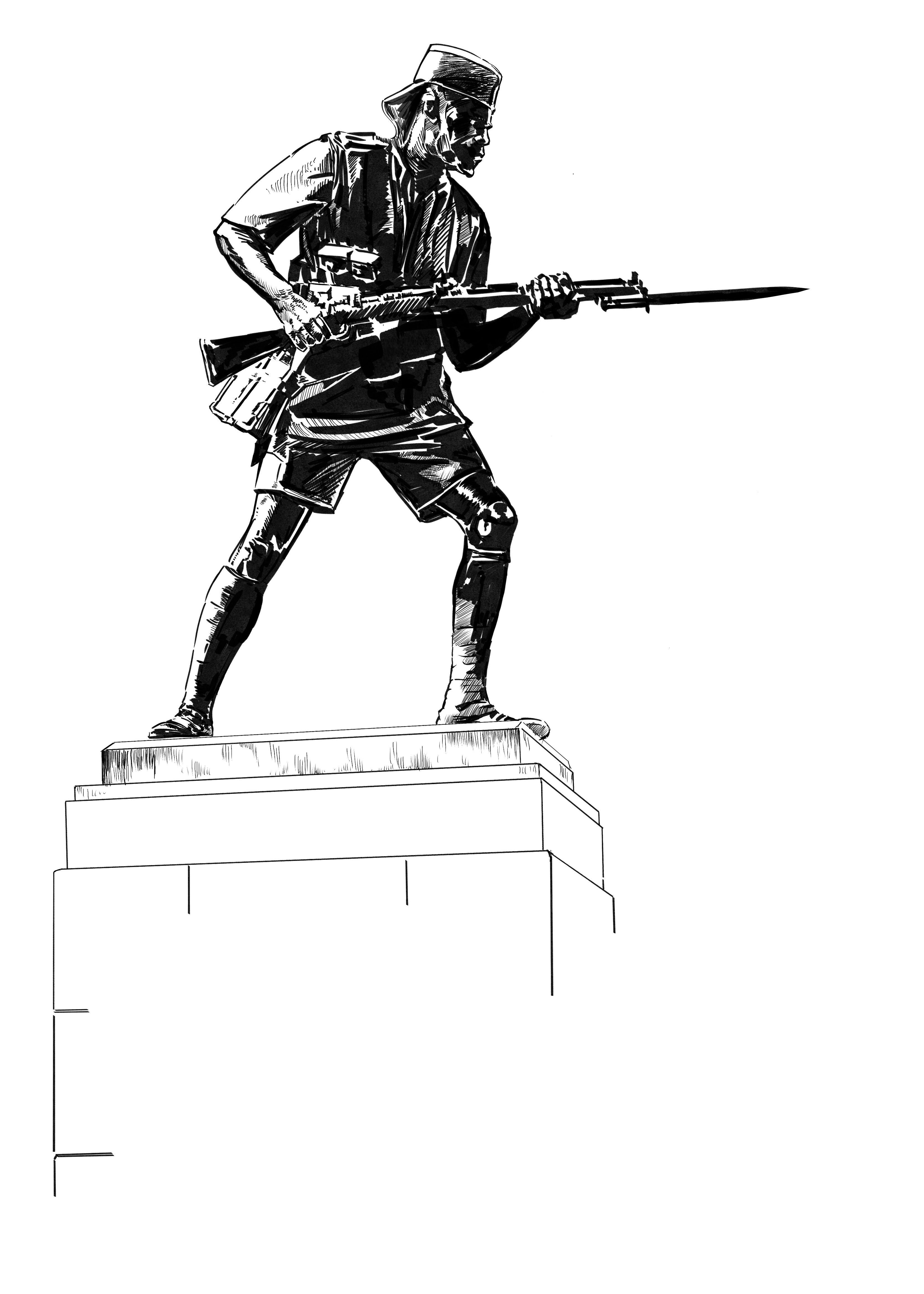

When the German East Africa Company (DOAG) arrived in 1887, the Old Boma, the oldest surviving building in Dar es Salaam dating back to the 1860s when the city was first established under Sultan Sayyid Majid bin Said of Zanzibar, was repaired and expanded. A year later, in 1888, the Sultan of Zanzibar formally transferred the administration of the mainland coast to DOAG as a protectorate. However, this move sparked resistance, culminating in the Abushiri Revolt in January 1889. To defend against the uprising, the Germans fortified the Old Boma and its neighboring buildings with walls and bastions, transforming them into a defensive fort. The revolt was brutally suppressed, leading to the German Empire assuming full control of what is now Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi, turning the former protectorate into the colony of German-East Africa.

In 1891, shortly after the war, the German colonial administration moved from Bagamoyo to Dar es Salaam, marking the beginning of the city’s structured urban planning and expansion. The Old Boma, now part of the German Imperial Navy’s property, was used as a barracks, customs office, and prison. By 1903, the Old Boma no longer met the German colonial authorities’ standards for an administrative building, leading to the construction of the grand Bezirksgebäude (now Dar es Salaam City Hall) next to it. By 1907/1908, the building also housed police offices and a prison specifically for Europeans.

Photo (c) DARCH

During World War I, British forces took control of Dar es Salaam in 1916. The fortified complex, including the Old Boma, remained largely intact and was repurposed as a police station under British rule. After Tanzania gained independence in 1961, the Old Boma was used by various government institutions, including the Forestry and Antiquities Departments. In the 1970s, it was leased by the Tanzania Publishing House before facing demolition threats in 1979 to make way for a hotel development. Local advocacy efforts saved the building, leading to its conservation and renovation in 1981 under UN-led initiative.

Despite its heritage status, the Old Boma faced further threats in 2012 when plans were proposed for extensive street development in the surrounding area. After prolonged discussions, the planned roads were rerouted to preserve the building. Amidst this modern expansion of Dar es Salaam as one of Africa’s largest cities, the Old Boma remains one of the few historic buildings still standing along the harbor. Recognizing its significance, the Dar es Salaam City Council, Architectural Association of Tanzania and Technical University of Berlin, initiated a detailed architectural study in 2015, coordinated by the Dar Centre for Architectural Heritage (DARCH). After extensive restoration work funded by the European Union, the Old Boma reopened to the public in 2017 as a visitor center with exhibitions on Dar es Salaam’s history and architecture, a rooftop café, and various visitor facilities. Its preservation ensures that this historic structure, which has withstood over 150 years of change, continues to be a vital part of the city’s cultural heritage.

Several colonial traces remain at the Old Boma and its surrounding area, reflecting Dar es Salaam’s layered history under German and later British rule.

- The urban planning with its street patterns is still visible in the city’s central plan. The grid-like structure of streets radiating from the waterfront were established by the Germans in 1891. The British colonial government implemented racial segregation policies, leading to separate prisons for Africans, Indians, Arabs, and Europeans – a colonial legacy that shaped urban social structures.

- Dar es Salaam City Hall (Former Bezirksgebäude): Built in 1903 during German rule, this grand building next to the Old Boma reflects German colonial administration.

- Azania Front Lutheran Church: A landmark built in 1898 by German missionaries, still standing with its distinct colonial-era architecture.

- St. Joseph’s Cathedral: Constructed by German missionaries, this neo-Gothic cathedral is a prominent colonial-era structure.

- Old Post Office Building: A relic of German administration that later served under British rule.

- Central Railway Line: Originally built by the Germans in the early 1907-14, it remains a key transportation route, with stations reflecting colonial-era design.

- Dar es Salaam Port: Developed under German and later British rule, the port played a major role in colonial trade and exploitation.

Further Information

- Becher, Jürgen (1997): Dar es Salaam, Tanga und Tabora. Stadtentwicklung in Tansania unter deutscher Kolonialherrschaft (1885-1914), Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Brennan, James, Burton, Andrew & Lawi, Yusuf (2007): The Emerging Metropolis: A History of Dar es Salaam, circa 1862-2000, Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

- Hege, Patrick Christopher (2025): Dividing Dar: Race, Space, and Colonial Construction in German Occupied Dar es Salaam, 1850-1920, Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Seifert, Annika & Moon, K. (2017): Dar es Salaam. A History of Urban Spaces and Architecture, Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

- Grigoleit, Thomas (2023): Plattenbauten und Palmenkanonen: Zu Fuß in Tansania, Hamburg: tredition.

School Partnerships

There are more than 60 partnerships between Tanzanian and German schools. Some of them address the colonial past in project work, for example ‘City Research’ by students from Berlin and Dar es Salaam 2024. The resulting films about colonial traces in urban spaces can be viewed as part of the exhibition ‘History(ies) of Tanzania’ at the Humboldt Forum and online: www.humboldtforum.org/de/magazin/artikel/city-research.