Delphine Froment

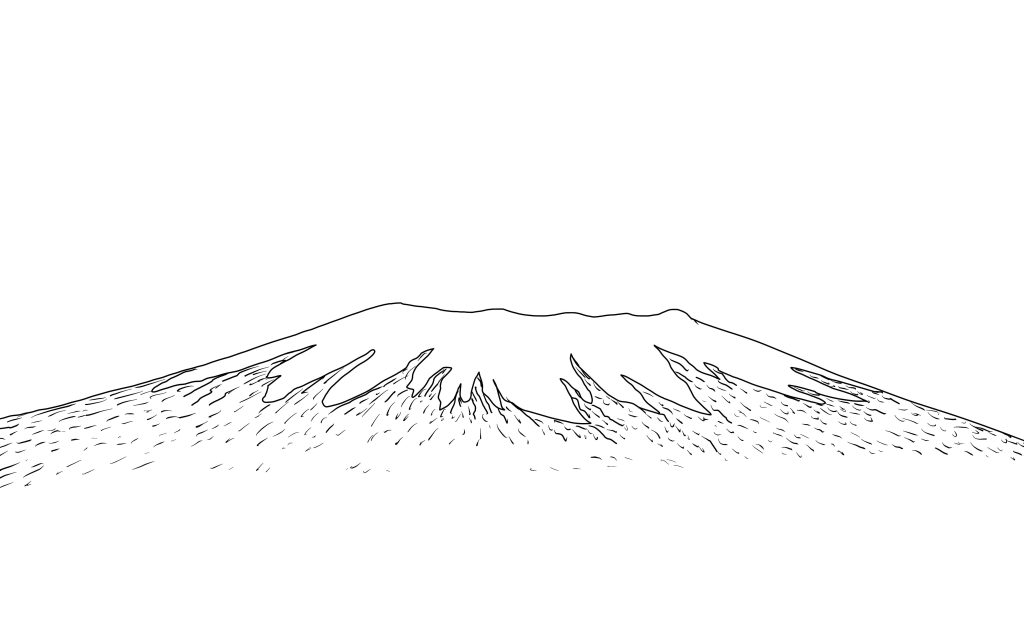

Kilimanjaro is one of Tanzania’s most iconic landmarks. At 5,895 metres, it is the highest mountain in the country and the roof of Africa, drawing climbers from around the world. The massif is an omnipresent symbol in Tanzania: from Air Tanzania’s slogan ‘The Wings of Kilimanjaro,’ to the ferries connecting Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar that are named after the mountain, and to the TSH 5,000 banknotes, the national coat of arms, and Kilimanjaro Lager Beer: All depicting its iconic snow-capped peak, Kilimanjaro pervades public life.

However, this economic and symbolic significance is directly inherited from the way Westerners perceived – and later imposed – a particular vision and use of the mountain within an imperial and colonial context. In guidebooks, the history of Kilimanjaro often begins in 1848, with the supposed ‘discovery’ of the mountain by the German missionary Johannes Rebmann. But this ‘discovery’ was solely European. The Chagga people, who live on the slopes of the mountain, were already familiar with Kilimanjaro: although they had never attempted to reach the summit, they ventured into its higher elevations for hunting and foraging, and used its forest resources for many purposes, including heating, construction, and beekeeping. Furthermore, Rebmann did not set off alone. He was accompanied by a guide and porters from the Swahili coast, who were already familiar with the region. In the mid-19th century, Kilimanjaro lay at the crossroads of caravan routes that had been developing and expanding for several decades, eventually linking the entire East African hinterland, from the coast to the Great Lakes region. The term ‘Kilimanjaro’ itself probably originated on the Swahili coast, where Rebmann first heard it before his 1848 expedition. The prefix kilima is often interpreted as the Kiswahili word for ‘mountain’, while the meaning of the suffix njaro remains debated (suggestions include ‘mountain of greatness,’ ‘mountain of the evil spirit,’ etc.). The Chagga people encountered by the first explorers did not seem to use this name for the mountain, sometimes preferring the place name ‘Kibo’ instead – which is now used to designate the main peak of the mountain.

This ‘discovery’ nonetheless caused quite a stir in Europe: Rebmann’s account sparked a debate on Kilimanjaro’s snow, settled only in 1862. However, this controversy drew attention to East Africa and prompted a major wave of exploration in a region that had until then been one of the least visited parts of the continent by Europeans. Around fifteen expeditions before the end of the 1880s tried to reach the summit: none succeeded, but they admired the prosperity of the Chagga people, fuelling colonial ambitions. In the mid-1880s, Germany and the UK clashed over Kilimanjaro, which was ultimately ceded to German East Africa. The border between Kenya and Tanzania bears witness to the colonial disputes between Europeans. Although it follows a straight line from the Indian Ocean to Lake Victoria, it makes a marked deviation around Kilimanjaro – precisely because the mountain represented a significant geopolitical issue. Amid this rivalry, in 1889, German explorer Hans Meyer was the first to reach Kilimanjaro’s summit. He renamed it ‘Kaiser-Wilhelm-Spitze’ in honour of the German emperor, to whom he brought back a stone he had chipped off at the peak – thereby firmly establishing a German presence on the roof of the continent.

During colonisation, Kilimanjaro emerged as a key economic hub and a centre of European influence in East Africa, its favourable climate and abundant resources drawing missionaries, civil servants and settlers alike. It witnessed the growth of a thriving coffee industry. By the early 1910s, a paved road, a railway and a telegraph line linked it to Tanga on the coast, making it one of East Africa’s best-connected regions to the global economy. Simultaneously, Kilimanjaro grew into one of East Africa’s most iconic leisure destinations, attracting tourists keen to catch at least a glimpse of the mountain on safari and, ideally, to scale its heights. This burgeoning tourist economy swiftly capitalised on hotel infrastructure, an alpine club (the Kilimandscharo Bergverein, founded in 1913) and the route of the first climbing trail to the summit, complete with several mountain huts along the way.

However, tourism remained limited, with only three hotels by the end of German rule, and about a hundred climbs during the British Mandate – turning the mountain into an exclusive preserve for wealthy Westerners. Initially unfamiliar with this Western approach to the mountain, African communities were not mere bystanders in this tourism; they quickly became key participants: from the turn of the 20th century, alongside their farming activities, some Chagga people started working as guides, porters or cooks, assisting Westerners on their ascents. In so doing, they gradually adopted European mountaineering practices and ideals – as seen in the 9 December 1962 expedition, when, on the first anniversary of independence, a Tanganyikan team planted the national flag and lit a torch on the summit, which was newly renamed Uhuru Peak, the ‘peak of freedom’.

Beyond the symbolism of this celebration, which elevated the massif into a powerful emblem of the new nation, Kilimanjaro became central to Tanzania’s tourism policy from the 1970s. An international airport was built in Arusha in 1971 and the National Park was established in 1973, continuing the conservation policies imposed during the colonial era which had included several forest reserves. Opened to the public in 1977, with new climbing routes and additional facilities, the park began to attract steadily increasing numbers of tourists, reaching mass tourism levels by the turn of the 21st century. Today, the mountain welcomes around 50,000 visitors each year – including 35,000 who attempt the ascent – generating annual revenues of 55 million US dollars.

Yet while Kilimanjaro has become a major asset for Tanzania’s tourist economy, this has come at the cost of expropriating local communities, who have been deprived of many of their long-established uses of the massif from the forest belt (msudu) upwards. Above 2,000 metres, the mountain is now reserved for a specific form of economic exploitation – devised in a colonial context and shaped by Western norms to serve Western interests – in which the presence of the Chagga people is tolerated only when it conforms.

Other local uses of the mountain remain invisible: a situation that could be further exacerbated by a cable car project. Under consideration since 2019, this cable car would allow visitors to reach 3,700 metres in around 30 minutes, significantly reducing the ascent time. While helping to fulfil tourists’ dreams of climbing, this project risks undermining the economic system on which many local tourism actors now rely. Displacing certain groups (primarily Tanzanians) in order to make room for others (primarily Westerners), would be continuing a dynamic that dates back to the early days of imperialism.

Further Information

- Wimmelbücker, Ludger (2002): Kilimanjaro. A Regional History. Production and Living Conditions, c. 1800-1920, Münster, Lit Verlag.

- Bender, Matthew V. (2019): Water Brings No Harm. Management Knowledge and the Struggle for the Waters of Kilimanjaro, Athens, Ohio University Press.

- Clack, Timothy A. R. (2007): Memory and the Mountain. Environmental Relations of the Wachagga of Kilimanjaro and Implications for Landscape Archeology, Oxford, Archeopress.

- Clack, Timothy A. R. (ed.), 2009, Culture, History and Identity: Landscapes of Inhabitation in the Mount Kilimanjaro Area, Tanzania. Oxford, Archeopress.

- Hamann, Christof & Honold, Alexander (2011): Kilimandscharo – die deutsche Geschichte eines afrikanischen Berges. Berlin, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach.