The Tendaguru Expedition in Lindi: History of the Dinosaurs Bones, Debate of their Restitution and the Current Situation

Acquillina Melchior Rweyemamu

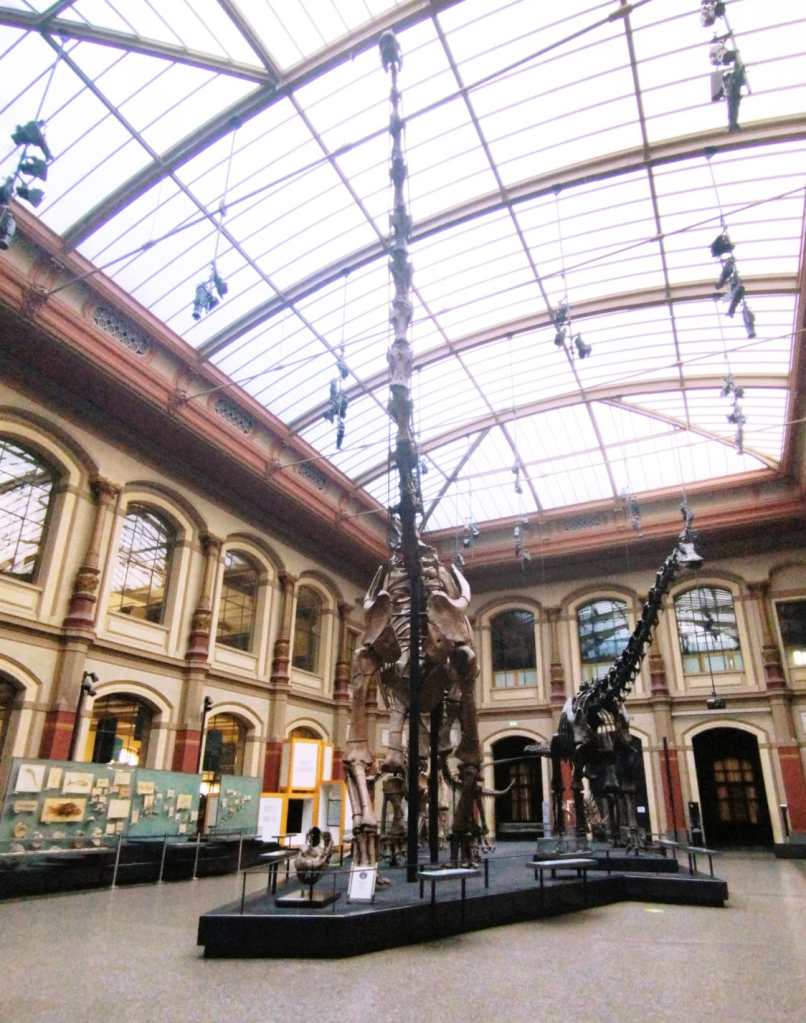

The Tendaguru Expedition (1909-1913) was one of the biggest paleontological expeditions of the 20th century. It was led by German scientists and palaeontologists, in Tendaguru at Lindi, the southern region of now Tanzania, formerly German East Africa. The German engineer Bernhard Sattler who was the director of the Lindi Prospective Company (Schürfgesellschaft), was searching for minerals to save his company after the Maji Maji war, but he ended up with dinosaur’s bones after being guided by the local Tanzanians where to find them. Over 225 tons of fossils were excavated and transported to Germany, including the famous Giraffatitan brancai dinosaur skeleton, which is still housed in the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin.

While fossils are celebrated in Germany as a scientific achievement, the excavation relied on the labour of local Tanzanians, often under forced conditions, whose contributions are not acknowledged. The fossils have been viewed from a European perspective, ignoring the colonial history and the cultural importance of the site to Tanzanian communities. For most Tanzanians, the expedition symbolises colonial exploitation, cultural loss, and economic injustice. Recently, there’s been a lot of discussions on decolonising museum collections, such as the 2018 Sarr and Savoy report, which call for African artefacts and colonial objects to be returned, and museums to work more with indigenous communities.

Restitution Demands and its Dilemmas

The restitution of the Tendaguru fossils remains an unresolved and complex issue. Although no official repatriations have occurred yet, conversations about the issue are gaining momentum. While Tanzania has not submitted any formal restitution claims, its officials, the media, local communities, and politicians continue to advocate for the return of cultural and historical artefacts, drawing attention to historical injustices and disputed ownership. The Tanzanian government has been reluctant to pursue repatriation, often raising the lack of facilities and resources to house the fossils, a valid concern. However, in 2020, a government official requested for transparency regarding the fossils’ provenance and initiated discussions about their return. Scholars have also proposed alternatives such as co-curated exhibitions, shared knowledge production, reciprocal training, mobile exhibitions, and digital repatriation, which offers virtual access to the fossils and their associated narratives. All these would promote more equitable cultural exchanges. Meanwhile, German museums face legal and political challenges, as fossils are often classified as federal scientific artefacts and human remains.

Status quo. Where are we now?

Until now in 2025, the Tendaguru fossils are still in Berlin, despite the growing global pressure to return them. Some African artefacts, like human remains and sacred items, have been sent back to the origin communities, but not fossils. They’re still seen as global scientific resources rather than cultural heritage. This has led to more open discussions about colonial history. Germany’s museum für Naturkunde introduced educational programs and tours concerning the topic, while Tanzania’s National Museum is building a heritage center in Lindi (www.nmt.go.tz/historical-centers/tendaguru-paleontological-site) and forming partnerships. Though it still faces issues such as limited funding, infrastructure, and expertise. With all that the big question remains: is symbolic recognition enough or is actual return needed?

Towards a Shared Future and Intercultural Inclusion

Meaningful restitution requires equality, ongoing dialogue, and collaboration. Museums must move away from colonial practices and involve source communities from the beginning. It’s great to see what steps are being done by Tanzanian and German experts by working together, but they need to make sure these initiatives become long term projects. For Tanzanians, the dinosaur fossils are seen to have monetary value that can help the community to develop their social and economic well-being, they represent cultural identity and colonial trauma.

Therefore, restitution should go beyond returning of the bones, but must include recognition of what happened, showing respect and mutual exchange. These fossils can help make museums more inclusive and globally responsible and inclusive space rather than a colonial object.

Further Information

- Chami, Maximilian Felix, Ndyanabo, Adson Samwel & Stoecker, Holger (2025): Finding Solutions for Managing, Protecting, and Promoting Tendaguru Palaeontological Site in Tanzania. In: Geoheritage 17, 44 (2025), online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-025-01092-7

- Heumann, Ina, Stoecker, Holger & Vennen, Mareike (2018): Dinosaurierfragmente. Zur Geschichte der Tendaguru-Expedition und ihrer Objekte, 1906 -2017. Göttingen: Wallstein / 2021: Vipande vya Dinosaria: Historia ya Msafara wa Kipalentolojia kwenda Tendaguru Tanzania, 1906-2018. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota / 2024: Deconstructing Dinosaurs. The History of the German Tendaguru Exhibition and Its Finds, 1906-2023, Leiden: Brill, online open access: www.brill.com/display/title/69712

- Nguyen, Thuy Ann (2022): Auf knochigem Boden, online: www.leibniz-magazin.de/alle-artikel/magazindetail/newsdetails/auf-knochigem-boden

- Podcast Geschichten aus der Geschichte (2020): Die Tendaguru-Expedition und das größte Dinosaurierskelett der Welt, Nr. 230, online: www.geschichte.fm/podcast/zs230/

- Virtual Access to Fossil and Archival Material From the German Tendaguru Expedition, online: https://www.museumfuernaturkunde.berlin/en/research/virtual-access-fossil-and-archival-material-german-tendaguru-expedition-1909-1913.